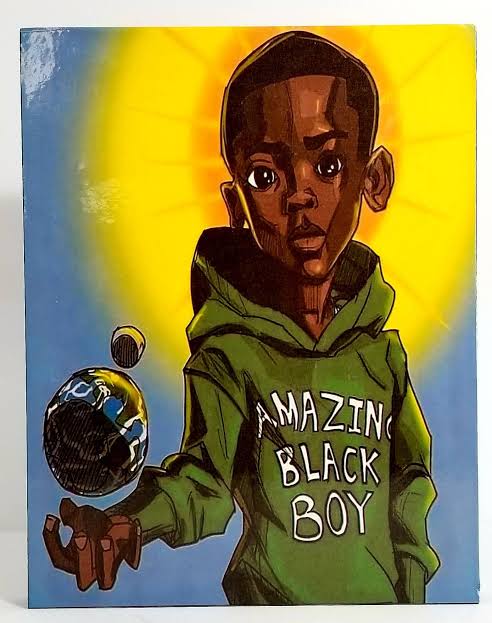

Short Stories

The African Boy

We welcome you to your Short Story column of the African Sunshine Magazine. We shall start by giving you a story, typical of African children, who, oftentimes, go through the thorns and brambles of life before making it to the top, if they ever succeed. We shall run the story in parts. Enjoy the read!

Part 1

I can’t consult my horoscope. The truth is that I don’t know my exact age. My birth certificate is lost. My father didn’t keep it.

My mother doesn’t have a clue about its whereabouts. What I do know is that my younger brother, Anthony, was born in 1960.

When I grew up to know the importance of the record of birth, I assumed that I’d be about two years older than Anthony.

I decided to set my own date of birth to 1958, October 10. I’ve been going about my adult life with this invented declaration of age.

I’m John Iroko. I’m a product of a broken home. I know poverty very well. I was born into a polygamous family under the discipline of a strict and violent father, a cocoa farmer. I’m the fifth child of my father’s six children. He had a girl by his first wife; a boy and two girls by his second; and me and Anthony by a woman who was my father’s third and last wife, Elizabeth, a housewife. My father loved his other two wives and their children, but he hated me and my mother - the recipient of my father’s violent behaviour. And why was my mother the target of my father’s aggressive behaviour? You may want to find out. Well, my mother dropped me a hint.

I was raised in a small town called Uso in Nigeria. The town had no benefit of electricity. Everyone relied on candlelight, torch-lights and lanterns at night. Roads and streets were dirty and dusty in the dry season. It was common to find heaps of rubbish of yester years uncollected. In the rainy season, the roads were muddy and flooded which made them unsafe for children. When the weather was windy, the moan of the wind in the surrounding forest was like the distant singing of a group of sinners confessing their sins to God.

I lived with my parents in a large mud house with bamboos as beams and a corrugated iron roof. Each of my father’s three wives had a room and a parlour to herself and her children. Dung of cows and goats was used for plastering the interior walls. On the outside, the walls had rough surface where thousands of cold-blooded lizards could be seen warming themselves in the early morning sunshine. By the evening they’d all go to sleep in the narrow gaps in the walls. To warm the house in the rainy season, we’d stoke fires in the middle of the rooms. Anthony and I usually sat opposite a bright fire, staring at the flames. Around the house, my father built a mud fence (ten feet tall) on which several thousand pieces of broken bottles were laid to deter intruders from climbing over it. And along the fence line, my father grew tobacco plants whose pungent aroma helped to keep snakes away.

It was in this house as I have described it to you that my father ruled his family with an iron fist and kept his wives like rusty coins which can’t be put into circulation. But in our district, my father came across as a wise man. Sometimes in the afternoon when he was not on the farm and the weather was clement, my father would sit in the shade of a leafy mango tree in front of our neighbour’s house and listen to world news in the local language on his World Receiver transistor radio. To give my father his due, you could count on your fingers the number of men in the town who listened to national and international news as my father did. It’s not at all surprising that young people, for their own benefit, would sit with him under the tree to get the lowdown on the latest national and international affairs. Some would pour out their troubles to my father for his advice.

I started primary school at the age of six. Time has left a gap in my memory about what actually happened on my first day at school. But I remember that in order to determine if I was ripe (age-wise) to start school, I was taken before the headmaster of the only primary school in the town. He asked me to stand erect, head straight, and to stretch my right hand over my head to touch my left ear. And having successfully carried out the exercise, I was offered a seat in a classroom of about twenty pupils.

Life was very hard for me in my childhood. It was hard to find food to feed my hungry month. Hunger and the fear of my father’s violent behaviour interfered with my ability to concentrate at school, as time went by. Sometimes, I sat down listlessly on the school premises, or walked in circles, trying to search the glass cell of my memory for a particular incident which would suddenly recall to me the moment when I had shared a laugh with my father.

To be continued.